Remember when you were in grade school? You could turn a box of wooden blocks into a city, a lump of clay into a superhero, a throwaway cardboard box into a formidable fortress. A giant box of crayons was all you needed to capture the world.

The instincts that drove your creativity were not in any way thwarted by the fact that your parents were in charge and made many decisions that affected you. They were the bosses and the administrators of discipline. Still, your imagination soared without limits and you were encouraged to flex your creative muscle.

Somewhere along the way, though, in the process of ‘growing up’ and learning the ‘rules,’ you abandoned your building blocks and clay. You exchanged your multi-colored crayons for a ballpoint pen.

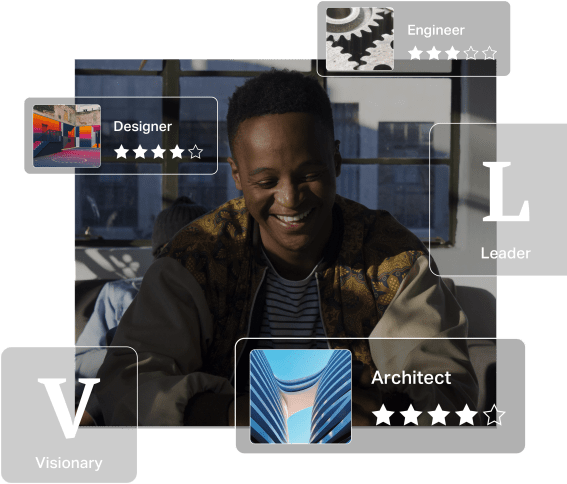

And now, perhaps, you find yourself in a nondescript cubicle doing nondescript work that asks nothing of your inherent imagination. This is not to say that you are in the wrong job. In fact, your job may be a perfect match to your skills. What is probably missing, though, is the opening to apply your unique genius.

As Sokanu data has revealed, ‘control and creativity seem to make us like work.’ This revelation presents challenges to both employees and employers. For employees, the task is to recapture the level of creativity with which we are all born, but which over time has likely been stifled by social and corporate structure and stricture.

In the workplace, employees cannot achieve this objective on their own. It can only be realized when leaders of organizations are flexible, willing to examine corporate culture, and determined to support the three psychological needs of every human being: to feel autonomous, to feel competent, and to feel related to others.

While encouragement from company principals is imperative to ignite the ideas of the teams they lead, there are ways for individuals to begin to rediscover and rekindle their own ingenious souls. Not unexpectedly, the simple abilities and energies of childhood are at the root of this process.

Before the adult world introduced us to conformity and led us to smother our sparks, we almost unknowingly generated idea after idea. We were endlessly curious, with an insatiable desire to know about the world. We were open to people and to their ideas, allowing us to explore new paths and diverse opinions. We were unafraid to step out on the proverbial edge once in a while, because we knew that’s where the biggest ideas and payoffs are. We had boundless stamina for life, for helping others, and for moving and thinking.

Curiosity, openness, risk tolerance, and energy – these are the perennial cornerstones of creative thoughts, ideas, and living. Once we reclaim them, through our personal intentions, by our deliberate actions, and with the advocacy of our leaders, we are ready to create again.

The work for employers and managers in this quest is to transition from directing and dominating to participating and facilitating. This process is very similar to the one undertaken by parents. As their children grow up, parents gradually loosen the reins to allow them to imagine, explore, and create their own futures. They never abandon their children. They just learn how to moderate structure and how to eventually let go, so that a functioning, self-expressing, and contributing adult can emerge.

In a similar way, to get the best their employees have to offer, corporate leaders need to integrate the traditional hierarchical mode of conducting business with the more inclusive ‘community’ mode, in which the voice of the highest ranking member carries no more weight than that of the lowest.

In his book ‘A World Waiting to Be Born – Civility Rediscovered’ author M. Scott Peck, M.D. defines community as ‘a structured or disciplined form of communication and a way of being together.’ He goes on to say, ‘Structure is the organizational incarnation of discipline.’ ‘Liberty without discipline is license for destruction.’

In other words, employee control and creativity (liberty) without leadership (discipline) is organizational anarchy (license for destruction). The key is to combine hierarchy and community, not to replace the former with the latter. It is this balance which gives license to both the mentors and the mentored to abandon hesitation and make the workplace that which it is meant to be: a haven for the preparation, incubation, illumination, and implementation of ideas.

Business leaders that commit to introducing the community mode to their organizations must subsequently face the question of how to do so. The integration of two diametrically different structures would appear to be a rather complex undertaking. In fact, this is not the case. As Dr. Peck points out, civil and intelligent organizations alternate between a hierarchical mode and a community mode.

Flexible executives instinctively learn which structure to use when. Typically, long-range planning, decision making, and organizational morale issues are best dealt with in a community mode. More immediate operational decisions are better made in a hierarchical mode.

The success of this two-faceted approach depends largely on the configuration of personalities and power within the organization. Simply put, if the man or woman at the top values community in the workplace, any resistance down the hierarchy can be overcome.

Extending control to employees so as to unleash their innate creativity is a noble goal. When embraced as a fundamental part of corporate vision, strategy, and will, it is much more. It is entirely possible. It is undeniably exciting. It is potentially transformative. And, perhaps most surprisingly, it is not that complicated.